“If we knew what we were doing, it wouldn’t be called research, would it?”

This quote from Albert Einstein rings perhaps a bit too true in the world of healthcare AI. At this point, there’s no denying the benefits of AI for behavioral health providers and clients. But there’s also no hiding the gaps in evidence validating AI’s effect on the care process—positive and negative.

The technology is simply too new—and the scientific process too slow. Plus, we have to use AI in order to study it—which puts healthcare providers in a tricky position. How can they responsibly integrate a tool that is still being researched (and developed) into the care process—and who shares in that responsibility? Their employers? Their professional associations? The vendors building the tools?

According to the panelists in our most recent webinar, “Evidence Meets Innovation: The Crucial Role of Clinical Research in AI Development for Behavioral Health,” the answer is all of the above.

Co-hosted with the National Council for Mental Wellbeing, this session offered a glimpse into the current body of research supporting AI in behavioral health. It also highlighted the gaps and opportunities—and took an honest look at how vendors, providers, researchers, and other industry stakeholders must work together to move AI research forward.

Check out the full webinar recording here, or read on for a quick summary of what was discussed. (Curious how Eleos is answering the call for more high-quality AI research? Peep our Science page for a full rundown of our published papers and studies in-progress.)

What is the role of scientific evidence in healthcare AI accountability?

Not all research is created equal.

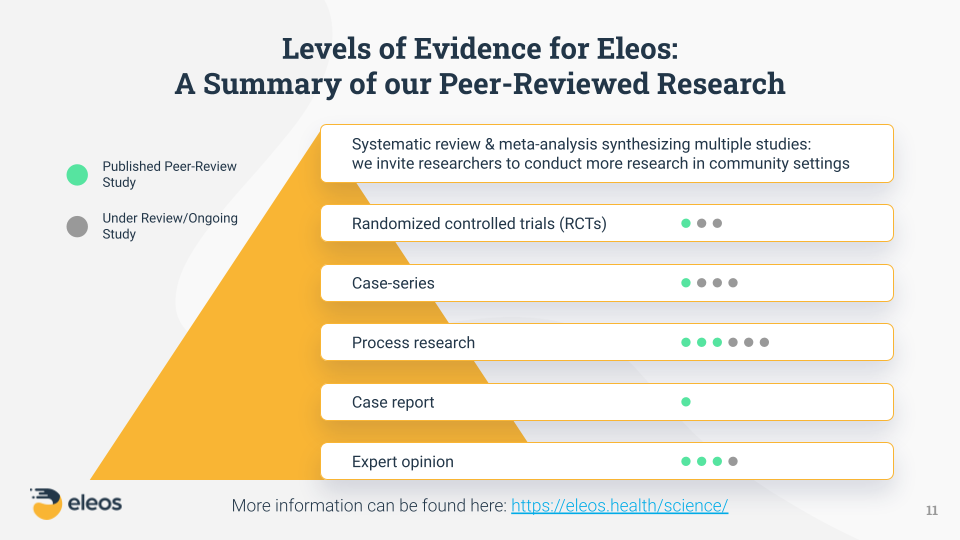

As Shiri Sadeh-Sharvit, PhD, Chief Clinical Officer at Eleos, explained during the presentation portion of the webinar, scientific evidence is divided into several different levels—what’s often called the “hierarchy of evidence.”

These levels range from expert opinions and individual case reports (shown at the bottom of the evidence pyramid below) to randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and systematic reviews (shown at the top).

For a deeper explanation of each level, watch the video clip below.

Despite being a fairly young company, Eleos has done a lot of research work across multiple levels of evidence—a true testament to our respect for, and dedication to, scientific research from the very beginning. As Dr. Sadeh-Sharvit noted, this is exactly what behavioral health providers and organizations should expect from any tech vendor they choose to work with—especially in an emerging space like AI. “This type of scientific rigor ensures the value claims that the company is making have been vetted by experts in the field and have reached a specific standard,” she said.

For example, when we say Eleos reduces documentation time by 50%, doubles client engagement, and drives 3–4x better symptom reduction, we have scientific evidence to back up those statements—including a published, peer-reviewed RCT study. And any AI vendor making similar claims should have the same.

But, all levels of evidence offer scientific value.

The great thing about research in the lower levels of evidence is that it often brings to light important questions that still need to be answered, informing future research “up the chain.” As Dr. Sadeh-Sharvit pointed out, vendors and other organizations often begin their research efforts at the lower levels and naturally progress up the hierarchy based on their findings.

At Eleos, the more we’ve grown, the more data we’ve collected—which means we can draw from a larger, more diverse data sample for each study. This strengthens the accuracy, reliability, and applicability of our findings. In fact, we consider our growth a calling to conduct more and deeper research, because we feel it is our responsibility to the behavioral health community to leverage our datasets in a way that will move the entire industry forward and enhance our collective understanding of AI best practices.

What are the biggest healthcare AI concerns?

Biases in AI are inevitable.

Despite the growing body of AI research and evidence, problems like bias still exist. AI isn’t perfect, because humans aren’t perfect. We know that—but it can be an uncomfortable truth to accept. Even if we’re confident that the benefits outweigh the drawbacks, it can be tough to reconcile things like decreased burnout and improved efficiency with the potential for biased or inaccurate AI output.

“Every AI algorithm is susceptible to bias—which is the tendency of AI systems to reflect human biases that are present in the world, and therefore present in the training data or the model design,” Dr. Sadeh-Sharvit explained.

While there are certainly steps AI developers can take to mitigate bias—such as actively monitoring output with a critical, clinically informed eye and using large, highly diverse datasets encompassing a variety of populations and ethnicities—there’s no scientifically proven way to remove it completely.

This puts providers in a tough position, because in a sense, they are all beta testers for a type of technology that has yet to be fully vetted and understood by the scientific community. On the flipside, issues like bias reinforce the crucial need for humans to remain in the AI driver’s seat. Providers cannot passively accept everything AI tells them—and AI certainly can’t replace them as experts. The technology simply isn’t capable of recognizing and correcting its own errors.

“Yes, it’s helping us; yes, it’s a tool—but we as clinicians signing off on the note need to read the note, we need to make sure it reflects the session, we need to make changes and edits to it where it doesn’t,” said webinar panelist Ashely Newton, CEO of Centerstone’s Research Institute. “Don’t just let it take over and not ever go back through and read it to make sure it’s correct. There’s a balance there between how much we write ourselves versus how much we’re reviewing and approving.”

Provider-centered platforms help prevent over-reliance on AI.

Keeping human experts in the loop is also the key to avoiding over-reliance on AI tools—another common concern brought up during the webinar. Some industry leaders worry that the advent of AI documentation is detrimental to skills like critical thinking, which are essential to creating high-quality notes and delivering high-quality care.

But as panelist Joseph Parks, MD, Medical Director at the National Council, pointed out, notes today are already different than they were 30 years ago. They “are flattening,” he said, and while AI will certainly have a further effect on note style, he and the other panelists resoundingly agreed that the benefits of spending less time on the task of writing notes far outweigh the costs.

“It’s hard to pay really precise attention at every moment with a patient,” Dr. Parks said. “I need all the help I can get.”

Plus, as the panelists emphasized, you’d be hard-pressed to find a behavioral health provider who enjoys the administrative side of the job. Most of them entered the field so they could spend their days helping people—not typing out how they provided that help. Paperwork is seen as a necessary evil, and AI—as moderator Dennis Morrison, PhD, put it—is a way to “get the junk off our desk.”

As Newton explained, behavioral health work is already hard enough without the documentation piece, and AI tools like Eleos offer a way to “make hard work easier.” Considering the high burnout and turnover rates plaguing behavioral health, the value of increased job satisfaction cannot be understated.

Session-specific AI output is the key to avoiding note homogeneity.

The group also weighed in on the commonly cited problem of AI note homogeneity—a concern easily put to rest by tools like Eleos, which create unique output for each individual session. (Though it’s worth noting that not all AI solutions can say the same, as many create notes based on pre-programmed templates rather than unique analysis of each session.)

“As we see clinicians utilizing tools like this, we actually see more individualized notes, because they better reflect the content of the session for that particular client,” Newton said, adding that the end result is often better than what clinicians write using templates and other supportive tools.

Dr. Parks echoed Newton’s assessment, reinforcing that this isn’t a new problem in behavioral health. Documentation is one of the least-liked parts of the job, so it’s no surprise that note-writing shortcuts like pull-forward and copy-paste have led to duplicate or highly similar content between notes—even before AI entered the equation. “We already have repetitive notes that are cut and paste, and part of that is that many of us build our own templates…and all of us have certain stock phrases that we apply repeatedly,” he said. “We’re fearing something that’s there already. This is a chance to have a better problem.”

Additionally, based on his current experience supervising about two dozen providers, Dr. Parks said there’s wide variability in the length and specificity of notes from one provider to the next. “It’s the three bears problem,” he said. “Some write too little, some just enough, and some write a book and it’s just too much. I look forward to programs like this that will help them write the right amount of detail.”

How can the healthcare community ensure responsible use of AI?

AI cannot—and should not—replace human experts.

One thing all of our panelists agreed on is the idea that AI is a provider tool—not a provider substitute. This can be a confusing distinction, because as Dr. Sadeh-Sharvit explained, “artificial intelligence” typically refers to the capacity of computers to simulate human intelligence—to mimic the way we think and make decisions. But most healthcare professionals prefer “augmented intelligence”—a flavor of AI that emphasizes the importance of the human using the technology.

“I think sometimes the language gets in the way of seeing the potential opportunity in front of us,” Newton said, referencing the nuance of “artificial” versus “augmented” intelligence. “It’s really not a replacement. Where we see the greatest opportunity is to become humans who use AI to do our work better or smarter.”

And that’s precisely our goal here at Eleos: freeing up providers to focus more on care.

“At Eleos, we are not aiming to replace therapists,” Dr. Sadeh-Sharvit explained. “We have developed AI to work in the background and augment how therapists are thinking—their clinical decision capacity. Our AI is designed as a companion. It’s not intended to replace the provider or their expertise.”

AI accountability is a shared obligation.

Whether we’re talking about ensuring the accuracy of AI-supported notes or simply using AI in an appropriate, secure, and ethical manner, the onus of responsible AI use ultimately falls on the behavioral health providers—and leaders—adopting the technology.

Dr. Parks likened AI to a clinical intervention whose effectiveness is still being studied. Unlike things like medical devices and medications—which must be proven and officially sanctioned by governing bodies like the FDA—decisions around the application of other clinical approaches often land with providers. “That leaves it up to us as licensed clinicians to decide if something is safe and efficacious,” Dr. Parks said. “I think often we don’t think critically enough about that. Whatever it is, what evidence is there that it worked—that it made a difference in people’s lives when reasonably applied?”

For providers wondering what other questions they should ask about an AI tool before using it, this article does a great job breaking down the most important boxes for an AI tool to check from the end user’s perspective.

Beyond scrutiny on the part of users themselves, it’s also critical for healthcare organizations to establish internal policies and processes governing staff AI usage—what solutions to use, when to use them, who to use them with, and so forth. According to Newton, this is where things like AI governance structures and policies become really important. “We need to be really leaned in together to be sure that we’re doing the right things along the way,” she said.

Need help creating an AI governance policy for your behavioral health organization? Get started with our free template.

Responsible AI use includes responsible vendor selection.

That internal set of guidelines must also address how the organization as a whole—as well as individual staff members—should approach adding an AI tool to their tech arsenal. Is there an official vetting process that must be completed, and if so, how is it initiated? How will leaders communicate and uphold these requirements? For vendors who are being considered, what standards must they meet? And of course, most importantly, where do empirical evidence and research fit into those criteria?

And vendors have a responsibility to provide solid, research-backed answers to those questions. “From a provider perspective, I do think the vendor selling the product has a responsibility to know, ‘Does this work—and does it work in the way that you’re telling me it works?’” Newton said. “I think it’s fair for a customer to be able to ask those questions and to expect that a vendor would have an answer, because we’re providers—not technologists. So, there has to be a way to bridge that knowledge gap. I see it as a shared responsibility and accountability around understanding what you’re purchasing and how you’re going to be using it.”

Wondering how to select the right AI platform for your org? Check out our list of seven AI vendor must-haves.

As AI evidence grows, responsible innovation will follow.

Technology, like clinical care, is always-evolving and always-improving—largely guided by new and better research. Unanswered questions are the lifeblood of scientific advancement, and while there are still plenty of answers to be found on the application of AI in behavioral health, it shouldn’t stop us from leveraging this technology in the ways we know are beneficial to providers, clients, and healthcare as a whole.

AI evidence, like AI itself, can only be improved by using the technology and studying the results—because, as Einstein would surely agree, we don’t know what we don’t know. That is the essence of research, and here at Eleos, we believe it is the essence of responsible and ethical AI use.

Ready to learn more about how Eleos Health’s evidence-based AI tools can enhance care delivery in your organization? Request a personalized demo here.