Originally published by Going Digital: Behavioral Health Tech on August 25, 2022

There has been a great deal written over the last two years about the increase in demand for behavioral health services (sometimes referred to as “the silent pandemic”) and the rise of virtual care like tele-behavioral health services. As it gets easier than ever for consumers to reach out for help and seek care with less stigma and more social openness, we are simultaneously facing a paucity of professional behavioral healthcare providers. Several recent publications by SAMHSA indicate we need 4.5M more clinicians to keep up with demand. The proliferation of virtual solutions and increased demand have exacerbated the shortage of clinicians and caregivers. In addition, the behavioral health market is moving to a quality-oriented model characterized by measurement, outcomes, and value-based reimbursement. In this article, we will propose a framework behavioral health providers can use to reconceptualize their care delivery models to both respond to the increased service demands and the shift to measurable quality.

What is this framework you mentioned that providers can use to respond to the increased service demands and the shift to measurable quality?

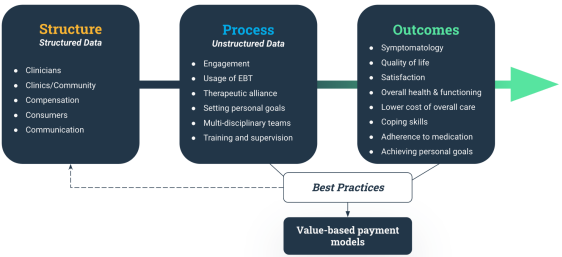

It is called the Donabedian model. The Donabedian model provides a helpful framework for understanding the components of delivering quality care. The model consists of three main components: Structure, Process, and Outcome. It has been widely applied in general healthcare since its inception in the 1960s, and efforts have been made to apply the model to behavioral health (e.g., NCQA, efforts with PCMH with distinction in behavioral health, HEDIS, etc.) but not very broadly or effectively.

Let’s dive into those three components. Tell us more about the “Structure.”

Structure = The Infrastructure Layer

Structure refers to the fundamental foundation for enabling the delivery of high-quality care, including facilities, equipment, and human resources, as well as policies for overseeing how care is administered and monitored. This layer is often described as the “availability of competent service providers and adequate facilities and equipment” (Donabedian 2005). It can be broken down into four main areas, or what we like to call “The Five C’s”:

1. Clinicians

- Years of experience

- Demographics

- Training received

2. Compensation

- The ability to provide good care and the best results can only occur if what is produced is valued and paid for adequately

3. Clinics/Community

- Care settings

- Organizational structure

- Facility size

- Staff and patient ratio

4. Consumers

- Demographics

- Comorbidities

- Access to care

5. Communication

- Electronic Health Record (EHR)

- Telehealth

- IT Stack, data protection, and privacy

In most cases, the structure layer is easier to measure, as its characteristics are binary – you either have it or you don’t. For instance, it is pretty straightforward to describe a typical community behavioral health organization that has 350 social workers and 10 MDs. The center has an EHR and delivers 60% of its services through telehealth. This center serves Medicare/Medicaid patients primarily, but they are also in-network with a few commercial plans. It has 10 locations, and 90% of its volume of services is through intensive outpatient programs (IOP).

And what about the “Process” of putting this model into practice?

Process = The Treatment Layer

While the presence of key structural elements suggests the capability of providing evidence-based, high-quality care, process elements assess whether the care being provided adheres to evidence-based criteria. “Several studies have conceptualized Process as the actual treatment stage in mental health service” (Badu et al., 2019). The Process is the heart of treatment; it is where the consumers and the behavioral health providers engage in a therapeutic conversation as a means of therapy. A few key areas to highlight are:

- Consumers’ participation in service delivery (engagement)

- Clinicians’ usage of evidence-based treatments (EBT)

- The therapeutic alliance (interpersonal relationship)

- Setting personal goals

- Multidisciplinary teams (integrated care)

- Training and supervision

- Adherence to medications

Consider the area of “Setting personal goals.” For most behavioral health providers, this involves identifying intra- or inter-personal conflicts and addressing them through various forms of psychotherapy. But recent research and our own experience have shown some interesting trends. For example, in our analysis of more than 20,000 real-world anonymized conversations, we found that 90% of behavioral health conversations cover at least one topic relevant to Social Determinants of Health (SDoH), and over 50% of those conversations cover more than four. These topics also take up a lot of time in therapy conversations. Based on our analysis of commercial populations, the clinician and member discussed SDoH topics 23% of their time together. Clearly, it’s not just the traditional inter-and intra-personal problems that are important to consumers. They need – and deserve – a comprehensive approach to address many problems simultaneously.

Additionally, the Process layer includes the operations associated with care. An example would be developing a treatment plan and accurate documentation of intakes, progress notes, and discharge plans that conform to evidence-based care.

The Process layer helps behavioral health providers to answer questions like: Are standard care guidelines being followed? Why is the member dropout rate so high? Which interventions are being used? How accurate is the documentation?

In some ways, the Process allows us to codify the best practices and replicate them across the organization. It helps clinicians focus on what matters most (providing quality care) and ensures every conversation counts.

As you previously mentioned, the behavioral health market is moving to a value-based model. What does the “Outcomes” layer look like?

Outcomes = The Improvement Layer

Today, different organizations measure different outcomes. For example, some organizations measure patient-reported outcomes (such as the PHQ-9 and GAD-7), and some measure consumer goals, hospital readmissions, or medical loss ratios. The goals outlined in Crossing the Quality Chasm (Institute of Medicine, 2001) will not be possible without measurement.

In the Outcomes layer, we ask ourselves: Do consumers get better? “The outcomes measure the effects of episodic mental health services on the well-being and health of individuals and populations” (Donabedian 2005). According to Dr. Harold Pincus, Vice-Chair of the Department of Psychiatry at Columbia University and a world-renowned expert in the field of quality improvement, behavioral health outcomes include:

- Patient-reported outcomes (symptoms)

- Quality of Life (highly connected to social determinants of health)

- Treatment satisfaction

- Improvement in overall health and functioning

- Lower overall cost of healthcare

- Enhanced coping skills

- Achieving personal goals

- 30-day rehospitalization

A recent survey found that only 16% of behavioral health providers use measurement-based care (“MBC”). The reasons for this are varied. For example, clinicians are not compensated for tracking these measures, consumers find them cumbersome, and clinicians question their value, especially when their time is already limited. This means that most of our outcomes data is partial at best and largely based on claims data, which is limited in only noting an event/encounter has occurred (does not provide information on the encounter’s content, nor a clinical assessment of the patient).

In behavioral health, a significant part of treatment is administrating evidence-based interventions in the form of a conversation. Compared to traditional medical care, which has a plethora of measurements and biomarkers, behavioral health care includes large amounts of unstructured data, much of which does not reside within the EHR. However, with advancements in Machine Learning (ML), encrypted and de-identified conversational data can be fully embedded into the clinical workflow providing a wealth of previously unavailable data and new insights to clinicians – without creating additional work for overburdened clinicians.

We at Eleos are in the business of providing Augmented Intelligence tools through technologies like Natural Language Understanding (NLU). As such, we’re strong advocates of these technologies. Our experience has shown that we can use this untapped resource of unstructured data to provide clinicians with perspectives on their treatments that were heretofore unavailable – we do so with superior accuracy and privacy.

What does this model look like specifically in the behavioral health industry?

From Structure to Process to Outcomes, where do we stand? It seems like much of the $5.1B of dollars spent on digital behavioral health in 2021 was focused on building a Structure – like developing networks and aggregating clinicians groups. But lately, we have seen a greater emphasis on Process and Outcomes. Marc D. Miller, President and CEO of Universal Health Services (one of the country’s largest providers), mentioned in his 2022 outlook to Behavioral Health Business that “2022 will mark a new focus on quality and outcomes. Digital and virtual-only point solutions in mental health and addiction will be commoditized as more comprehensive, multi-modal solutions deliver the quality and outcomes that are becoming the standard. Value-based care will continue to increase as quality and outcomes can be measured and rewarded by payors and patients alike” This shift has been articulated by payers and investors as well.

In the behavioral health space, the next big differentiation will be quality of care – a measurable Process that results in lasting Outcomes. While no one knows exactly how this will develop, the following framework might provide some direction:

1. Measure the Process

- Analyzing unstructured data sets is key to automating much of the operations around care and allowing clinicians to focus on clinical processes as much as possible.

- Focus on real-world data – data derived from several sources associated with outcomes in a heterogeneous patient population in real-world settings.

2. Measure the Outcomes (see above)

3. Extract and identify the relevant Process measures and codify best practices

4. Incorporate Process measures into the Structure

- Training purposes (how are staff trained/onboarded?)

- Supervision purpose (how do staff grow professionally?)

5. Demonstrate measurable Processes and lasting Outcomes

- Unlocking alternative payment models (e.g., value-based care)

In summary, the pandemic’s ripple effects will remain for some time – with more people needing health care services, but the supply will not increase anytime soon. Behavioral health providers are in short supply. To create a meaningful change, we must shift our focus from systems structures to measurable Processes that will provide real impact and real Outcomes.

Thank you, Dr. David Shulkin, Dr. Harold Pincus, Eric Larsen, Dr. Dennis Morrison, Dr. Dale Klatzker, Douglas Kim, Roy Wiesner, Dr. Nadav Shimoni, Jennifer Gridley, and Dr. Shiri Sharvit, as well as everyone else who contributed to this article.